An investigation into african art objects at UMMA — what we’ve found so far

An investigation into 11 objects of African art in UMMA’s collection has been unspooling online, allowing museum visitors and the public an unconventional first-hand look into how museums handle questions related to the ethical ownership of artworks.

While still ongoing, the investigation has led to troves of documents from UMMA researchers as they work to uncover the deep histories of these objects. You can read the full investigation reports in UMMA’s online investigation tracker and in person on the walls of the current exhibition Wish You Were Here: African Art and Restitution. We’ve summarized the major threads below.

BENIN BRONZES

Three of the objects being investigated fall into a group known as Benin Bronzes, a category of sculptures that originated in the 16th century West African Kingdom of Benin. Skilled guilds were contracted by the royal court in Benin City to create these brass—not as the name suggests, bronze—sculptures, which were put on the altars of deceased former Obas (kings) and Queen mothers, and decorated the walls of the royal palace. Many of these objects were stolen by British soldiers in a punitive expedition on Benin City in 1897. After decades of being held in museums across the Global North, Nigerian officials’ demand for their return are finally being heard.

Initial investigations into the provenance (or history of ownership) of two of the “bronzes” in UMMA’s collection found that the objects were donated by the son of Kurt Delbanco, who might have purchased them from Merton Simpson, an artist, collector, and dealer of African art. UMMA researchers unsuccessfully tried to locate Simpson’s records at the New York Public Library archives but ran into a dead end when the files were not found.

Unable to access the records, UMMA joined Digital Benin, an international project to digitally network the globally dispersed artworks from the former Kingdom of Benin. As part of the multi-national project, UMMA will submit photographs, information, and research about the objects to confirm whether they were part of the 1897 looting.

Condition reports and metal analyses of the third “bronze” sculpture in this investigation revealed that this object is more contemporary. This means it was not looted during the British punitive expedition and was created after 1897.

Follow this ongoing investigation

MUZIDI

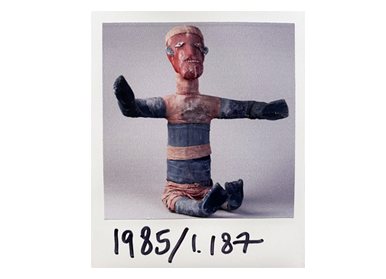

The Bembe used muzidi figures to represent and honor their ancestors. After the death of a revered individual, remains of the deceased are transferred into the muzidi reliquary receptacle, typically made from blue and red cloth. Common features include symbols drawn in chalk on the face and stomach, an open mouth with teeth, and outstretched arms. Once the spirit of the dead, or nkuyu, is transferred, the minkuyu (or plural form of nkuyu) reside within the figure, passing through an endless cycle of being. They are kept in relatives’ homes to serve as a tether between the living and the dead, where extended family can pray for protection, prosperity, or fertility of land.

Researchers have traced the history of the muzidi in UMMA’s collection to an unknown Swedish missionary who removed it from its place of origin between 1890 and 1914. Inconsistencies in record-keeping have been found, and it is unknown whether human remains are actually inside the object. While researchers were investigating best practices for how museums can most respectfully deal with potential human remains, UMMA finds osteological identification, such as CT or MRI scans, to be appropriate because it will not alter, damage, or otherwise invade the remains. UMMA researchers are actively working on arranging a date for scanning.

Follow this ongoing investigation

SHRINE FIGURES

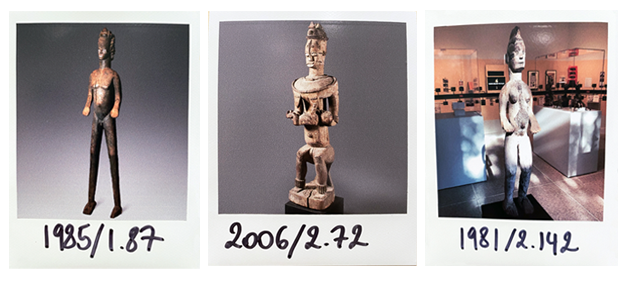

There are two types of shrine figures in this investigation. The first are alusi figures, which may represent several Igbo deities, spirits that serve as guardians for certain people and are associated with natural elements like earth and rivers. The Igbo statues in UMMA’s collection are among the largest sculptures of African art, carved in a standing position from iroko wood. If treated well with prayer and offerings, alusi brings peace, prosperity, and health. The second type are edjo re akare (spirit figures) of the Urhobo people of southern Nigeria.

Researchers kicked off the investigation into these objects by following three leads: 1) looking into the history of the donor; 2) learning more about the region of the world where the objects originated; and, 3) trying to learn more from Evan Maurer, the UMMA director at the time the objects were donated. Research into the donors led to a dead end, but conversation with Maurer helped researchers understand the shaping of UMMA’s African art collection at its infancy. They found evidence of one of the shrines photographed in situ by historian Perkins Foss in 1971. One of the alusi was identified by Prof. Herbert (Skip) Cole as carved by the artist Ubah (from Isuofia), hailing from a town south of Awka such as Isuofia, Adazi Ani, Nanka, Agulu or Neni.

Follow this ongoing investigation

MINKISI

Until the early 20th century, power figures, or minkisi, were used as intermediary vessels to communicate with the ‘otherworld’ – the world of the dead, of the ancestors, of the spirits. The wooden core of the statues are carved by an artist before the nganga, or ritual expert, attaches medicinal substances known as bilongo. Common additions included carefully picked leaves, beads, hide, metal balls, etc. It’s not until powerful medicine is added to the nkisi that the ancestral spirits contained in the figures are activated.

Researchers discovered early in their investigation that the minkisi in UMMA’s collection are complete, meaning they retain their spiritual power. They also discovered that all of UMMA’s minkisi were purchased from a Belgian art dealer named Marc Leo Felix. Researchers are currently investigating the best storage practices for ritually sensitive or sacred objects, looking at comparative examples such as the Native American Graves and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).

More from UMMA