A Scholar Riding on a Sword

Kanō School

Description

Kano School

A Scholar Riding on a Sword

Japan, Momoyama period (1583–1615)

Late 16th century

Ink on paper

Museum purchase for the Paul Leroy Grigaut Memorial Collection,

1969/2.89

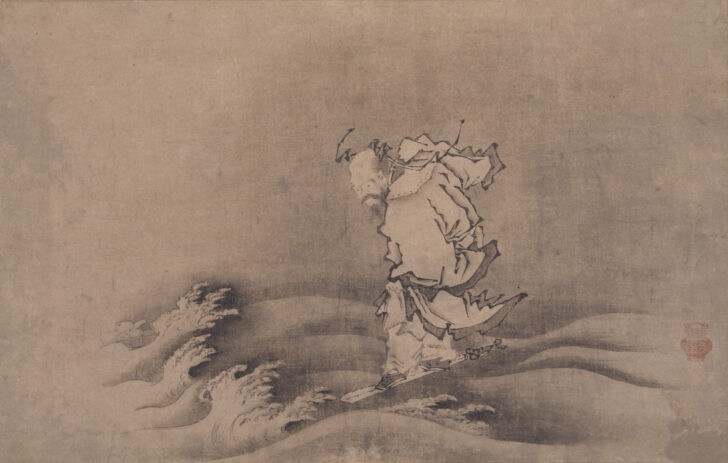

This painting, which is likely based on an imported Chinese model,

probably depicts Zhongli Quan (Shoriken in Japanese), one of the

eight immortals of Daoism, a Chinese philosophy and religion that

instructs believers on how to exist in harmony with the universe.

Zhongli is sometimes described as a warrior who had a magical sword

that could bear him across the waters. While Daoism was not practiced

in Japan, Zen Buddhists embraced the Daoist immortals as spiritual

models.

The painting’s seal identifies the artist as Kano Motonobu (1476–1559),

one of the leading artists working in Kyoto in the first half of the

sixteenth century. Though the seal is a later addition, the painting

may still have come from Motonobu’s workshop, or it may be the work

of a later follower. The Kano school was endorsed by the Tokugawa

Shogunate, the ruling family of the Edo period, and ink painting with

Chinese themes was one of its signature art forms.

Summer 2022 Gallery Rotation

__________

Buddhist teachings first arrived in China in the first century ce and from that point forward developed side by side with the two main streams of indigenous philosophy, Confucianism and Daoism. Relations between adherents of these schools of thought were often hostile, but during the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279)—when Zen monks, Confucian scholars, and Daoist thinkers were all drawn from the educated gentry class—there was a period of warm mutual respect. Under the rubric of the “unity of the three creeds,” Daoist subjects found their way into Chinese Zen circles, whence they spread to Japan. This painting, which is no doubt based on an imported Chinese model, probably depicts Zhongli Quan (Shôriken in Japanese), one of the eight Daoist immortals. (The attributes of the eight immortals are quite fluid, which is why the identification of the figure is uncertain.) Zhongli is sometimes described as a warrior who had a magical sword that could bear him across the waters.

The painting bears a seal reading Motonobu, referring to Kanô Motonobu, one of the leading artists working in the Japanese capital city of Kyoto in the first half of the sixteenth century. The seal is obviously a later addition, but the painting may come from Motonobu’s workshop or a later follower. Motonobu was not a practitioner of Zen, but as official painter to the ruling Ashikaga warlords, he had access to the Chinese painting collections of Kyoto’s great Zen temples, an invaluable resource when he was called upon to do Zen subjects. Motonobu’s descendants continued to paint Zen themes for Japan’s military aristocrats for the next several centuries.

Arts of Zen, Spring 2003

M. Graybill, Senior Curator of Asian Art

Subject Matter:

Buddhist teachings first arrived in China in the first century ce and from that point forward developed side by side with the two main streams of indigenous philosophy, Confucianism and Daoism. Relations between adherents of these schools of thought were often hostile, but during the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279)—when Zen monks, Confucian scholars, and Daoist thinkers were all drawn from the educated gentry class—there was a period of warm mutual respect. Under the rubric of the “unity of the three creeds,” Daoist subjects found their way into Chinese Zen circles, whence they spread to Japan. This painting, which is no doubt based on an imported Chinese model, probably depicts Zhongli Quan (Shôriken in Japanese), one of the eight Daoist immortals. (The attributes of the eight immortals are quite fluid, which is why the identification of the figure is uncertain.) Zhongli is sometimes described as a warrior who had a magical sword that could bear him across the waters.

The painting bears a seal reading Motonobu, referring to Kanô Motonobu, one of the leading artists working in the Japanese capital city of Kyoto in the first half of the sixteenth century. The seal is obviously a later addition, but the painting may come from Motonobu’s workshop or a later follower. Motonobu was not a practitioner of Zen, but as official painter to the ruling Ashikaga warlords, he had access to the Chinese painting collections of Kyoto’s great Zen temples, an invaluable resource when he was called upon to do Zen subjects. Motonobu’s descendants continued to paint Zen themes for Japan’s military aristocrats for the next several centuries.

Arts of Zen, Spring 2003

M. Graybill, Senior Curator of Asian Art

Physical Description:

This painting shows a scholar that is riding with his feet on a sword across waves. There is a seal on the lower right corner of the painting that reads Motonobu, referring to Kanô Motonobu.

Usage Rights:

If you are interested in using an image for a publication, please visit https://umma.umich.edu/request-image/ for more information and to fill out the online Image Rights and Reproductions Request Form.