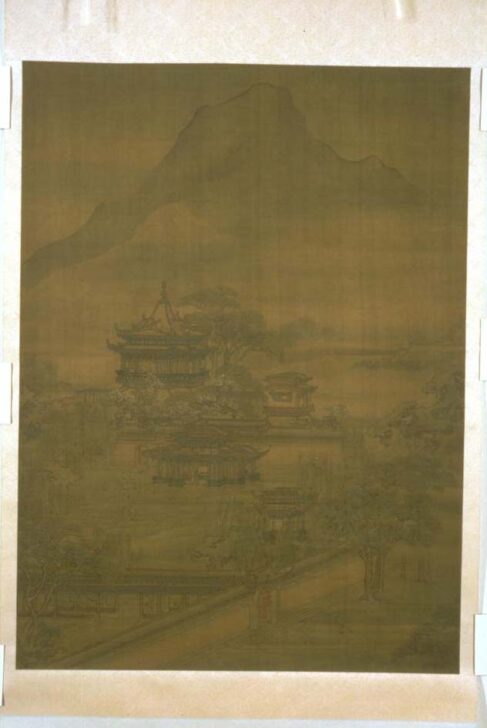

Spring Dawn at the Han Dynasty Palace

Yuan Jiang (Yüan Chiang)

Description

In Chinese painting criticism of the Song period and later, the work of "professional" painters—that is to say, those who earned a living by painting commissioned works—was often disparaged. By contrast, paintings by scholars (the "literati," in Chinese, wenren) was singled out for praise for being, like calligraphy, a sign of the superior gentleman's lofty spirit.

However, this biased history overlooks the important contributions of professional painters to the Chinese painting tradition. "Spring Morning at Han Palace" by Yuan Jiang is a fine example of the exceptional technical skill and sensitivity found in the best of professional painting. Yuan Jiang was from Yangchou, located by the Yangtze river between Nanjing and Shanghai. He specialized in large landscape paintings showing meticulously depicted palace buildings, but otherwise we know very little about his life and career.

In this painting, Yuan Jing executed realistic trees and gnarled rocks surrounding majestic imperial palaces with ornate roofs and meandering corridors. Drawn from the imagination of the artist, the narrative unfolds on a glorious spring morning at the height of the great Han dynasty. Evidence of spring is supplied by magnolia and lilac blossoms; morning is manifested by the grand madam on the top floor having her hair coiffed as maids brings tea. Outside, there are women gathered on the terrace enjoying the full-bloom flowers. A eunuch carries a branch of blossoms to a second-floor maid who prepares the receptacle. One maid with a zither walks along the covered pathway to the residence. In addition, servants are performing their daily morning chore of sweeping the ground outside the gate. The detail in this painting, such as the intricate architectural design, the lively figures, and even the subtle patterns on the bamboo curtains, captivates the attention of the viewer.

Yuan Jiang's painting does not bear a signature, which in this period was typically is inscribed in either of the upper corners. It is quite possible that the top section of the original painting was removed by an ignorant collector who did not recognize the importance of the artist's signature. Fortunately, the remainder of the scroll maintains its original silk with few restorations. It is the distinctive style and superb quality of this piece that establishes its authorship.

Marshall Wu

Senior Curator of Asian Art, 2000

Usage Rights:

If you are interested in using an image for a publication, please visit https://umma.umich.edu/request-image/ for more information and to fill out the online Image Rights and Reproductions Request Form.