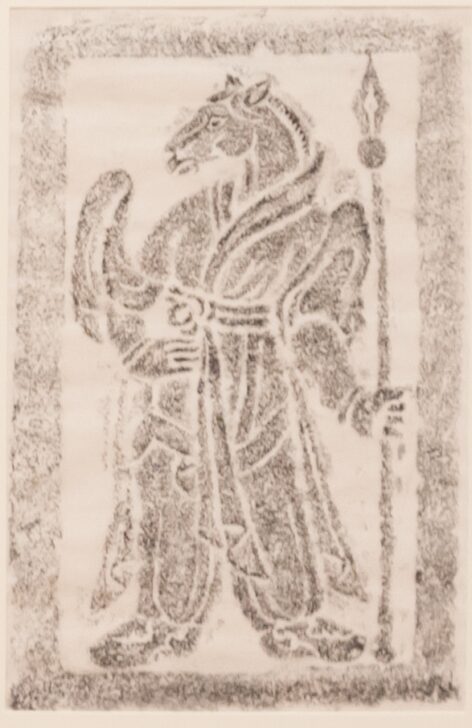

Twelve Zodiac Animals: Horse

Korean

Description

Rubbings of twelve zodiac animals from the tumulus

of General Kim Yu-sin 김유신 (595–673)

Korea, 20th century

Ink on paper

Stone reliefs: Unified Silla period (676–935)

Transfer from the Slide and Photograph Collection, Department of the

History of Art, 2021/1.128.1–12

These rubbings are taken from the reliefs on the guardian rocks (hoseok)

surrounding the tomb of General Kim Yu-sin 김유신 (595–673), a key

figure in the unification of the Korean Peninsula under the Silla during

the seventh century.

The reliefs are decorated with the twelve signs of the zodiac, depicted as

animal heads on human bodies. These signs are commonly associated

with a twelve-year cycle, each sign corresponding to a cardinal direction

and a time of day. While in China and Japan, objects bearing the zodiac

signs were often buried in tombs, the people of the Silla period in Korea

covered the exteriors of their tombs with rocks depicting the zodiac

figures, arranged as if they were guarding the deceased. Though zodiac

figures on guardian stones from the Silla period are typically depicted

in armor, the figures surrounding General Kim’s tomb are shown in

plain clothing and holding weapons.

Displayed as one of twelve prints.

(Korean Gallery Rotation, Summer 2025)

Subject Matter:

The horse is the seventh animal in the zodiac. Depicted in this stone rubbing, it is one of the guardians of the tomb of General Kim Yusin, either to protect the tomb from erosion, or to show a high level of honor as Kim Yusin was highly influential in the unification of Korea.

The symbol of the horse has many other associations, including being connected to the elemental power of fire and signifying the time between 11:00 and 12:59. People born in the year of the horse are said to be energetic and social, but can be self-centered and lacking self-confidence.

Physical Description:

This is a rubbing of a figure with the head of a horse dressed in robes. The left hand is holding a spear and the right hand is rested on the hip.

These rubbings are taken from reliefs of the twelve Chinese zodiac animal deities on the surface of guardian rocks (è·çŸ³, hoseok ) placed around the edge of the tumulus of General Kim Yusin (金庾信, 595–673) on Songhwasan Mountain (æ¾èŠ±å±±) in Gyeongju, Gyeongsangbuk-do Province. The twelve animal deities guard the twelve Earthly Branches which can be interpreted as spatial directions. Each animal deity has the face of a certain animal and a body of human. The twelve animal deities occur in the following order according to the Chinese zodiac: rat, ox, tiger, rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, rooster, dog, and pig. While the twelve deities on guardian stones placed around royal tumuli from the Unified Silla period are normally clad in armor, those carved on the guardian stones surrounding General Kim’s tomb appear in plain clothes and with weapons.

[Korean Collection, University of Michigan Museum of Art (2017), 221]

Usage Rights:

If you are interested in using an image for a publication, please visit https://umma.umich.edu/request-image/ for more information and to fill out the online Image Rights and Reproductions Request Form.