Approaching Art from the Outside with Professor Sascha Crasnow

“I do not believe guilt is inherited, but responsibility is, and there is nobody alive today whose existence has not been shaped by colonialist, racist forces. That is a legacy we all live with, and we should all deal with the consequences.”

–The Whole Picture, Alice Procter

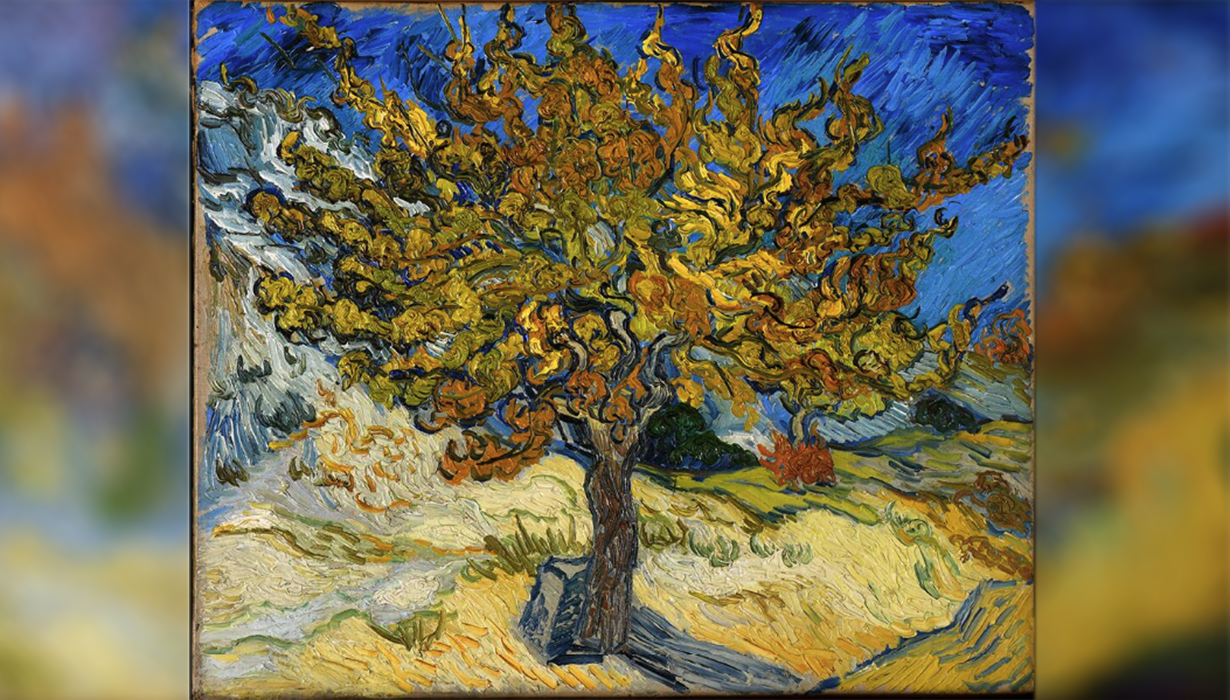

There is a painting in the Norton Simon Museum, a Van Gogh. Oil on canvas, painted in 1889, titled The Mulberry Tree. I recently had a conversation with Sascha Crasnow, a University of Michigan lecturer in Islamic Arts and Culture. To kick off the conversation, I asked her about a time when she was changed by a work of art. This is the piece she chose. The painting was a long time favorite of hers. She had graduated, was living in L.A., working in fashion, and, of course, trying to figure out what to do next. She drove herself to the museum, excited to be around art, and especially looking forward to sitting in front of The Mulberry Tree again. In front of the painting, she read Van Gogh’s letters to his brother, and she fell in love with the piece again.

This moment led her to pursue completing a masters degree in Art History, a PhD with a focus on Palestine, and her current position teaching Palestinian art, and the Arab-Islamic world more broadly, here at U-M.

While writing her master’s thesis on German artists, Sascha traveled to Palestine for the first time. While it hadn’t been a part of the world she much thought about before, seeing the apartheid wall was enough to make her want to know everything about the occupation. She had already been interested in the ways that artists responded to their political environments as well as generational shifts and when she applied for her doctorate, Palestinian art is what she decided she would work on.

In her own words, Sascha is a white, cisgender, secular Jewish woman. A cultural outsider within the field of Palestinian art, she knows that her identity grants her certain privileges, especially compared to scholars of Arab and Palestinian descent. Her Russian name, for example, is read as a Jewish one by Israeli authorities when she travels for research, and her American passport certainly helps as well.

APPROACHING ARTISTS

When she started her graduate studies, it was important to her that she learn Arabic. She told me that when she would approach artists, she would write emails in both English and Arabic as a way of acknowledging her position as an outsider and as an attempt to meet people where they are rather than insisting they come to her. Notably, most of the artists she met spoke fluent English, but she found the gesture to be effective. Studio visits would be conducted in English but the conversation had around tea afterwards would be Arabic. Because Professor Crasnow works with living artists, it was especially important to make sure that their understandings and interpretations are the ones being centralized.

One artist took her up on the offer to discuss the work in Arabic, although the artist was fluent in both English and Hebrew. She was a Palestinian artist living within the state of Israel (occupied Palestine) and she was excited at the prospect of having that conversation in Arabic. They spoke for three hours, entirely in Arabic, and Professor Crasnow recounts it as a challenging experience. She asked clarifying questions when needed, requested that words be repeated if she didn’t catch them and the artist, in turn, was generous with her time and patience.

IDENTITY AND PRIVILEGE

Professor Crasnow has responsibilities as a non-Palestinian studying Palestinian art and, clearly, she understands and accounts for them. We turned next to what she could do with her privilege for the people whose art she was studying.

In the U.S. context, Palestine is obviously a highly politicized subject and Professor Crasnow believes that having someone like her in the field, somebody who is not only a non-Palestinian, but also Jewish teaching a Palestinian perspective allows for an unfair perception, but a perception nonetheless, that anti-Zionism is not a “biased” perspective or a view exclusive to the Palestinian community. She can affirm, as someone who comes from a different background, that what Palestinians have been saying for so long is true.

It is quite possible that Professor Crasnow’s class is the only Palestinian art class in the country. I asked her if it felt like a heavy responsibility and she responded, “I feel lucky to be able to do it.” She feels a responsibility to do it well, to constantly improve it, and to provide any information that her students, Palestinian students in particular, are seeking.

This reminded me of a conversation I had with Jacob Sirhan, president of SAFE (Students Allied for Freedom and Equality, a Palestinian solidarity organization at U-M), a couple weeks ago when we were planning an event on Palestinian poster art. One of the posters that came up was this one.

|

| Franz Krausz (1905-1998), Visit Palestine, 1936 |

This is a famous poster among Palestinians because it reaffirms the existence of their homeland. It was originally a zionist poster, reclaimed by the Palestinian liberation movement. In fact, use of the poster was reclaimed by an Israeli anti-Zionist. I told Jacob that maybe we shouldn’t put this poster in the presentation since it was so well known already. I was surprised to hear that, although the poster was so famous, he himself had not known of its origins until he took Professor Crasnow’s class and we decided to keep it in the slideshow.

A PALESTINIAN AUDIENCE

Jacob is one of many Palestinian students who has taken and appreciated the class and the next topic I was curious about was what it was like teaching this subject as a non-Palestinian to Palestinian students. With all of her classes, Professor Crasnow told me that she tried to create a classroom environment where students with personal backgrounds or experiences that she did not have, as a result of being in an insider group that she was not part of, felt comfortable bringing it up and taking a leadership role in the classroom should they want to. Her class has definitely changed over the years with the insights these students have provided. This is also why she tries to include events and guest speakers as often as possible, always mindful of the fact that, no matter what, there is a perspective she will never be able to bring to the classroom.

NEUTRALITY AND BIAS

I’ve heard many times, especially in high school, about how teachers are supposed to maintain some sort of objectivity, to teach without bias. I’m sure many people think that Professor Crasnow, simply by teaching this class, is pushing a certain agenda and therefore failing to maintain that myth of neutrality. She responds to this first by establishing that the idea of scholars, teachers, and professors being objective rests on an impossible notion that any human being can remove themselves from their subjectivity. It’s impossible to detach yourself from your positionality and your worldview.

In the words of Desmond Tutu, “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.” The idea of a neutral or balanced perspective implies an even power dynamic. To play at neutrality in such a situation is to uphold that power dynamic, to be subjective. This is why, says Professor Crasnow, she doesn’t teach an Israel-Palestine class. She is teaching Palestinian art and in that class she is presenting the perspective of Palestinians. She does not present her politics, regardless of how obvious they become via what she chooses to teach. She is presenting their art.

COLONIALISM AND THE MUSEUM

Professor Crasnow also worked briefly at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Guggenheim in New York while she was completing her masters. The question of how to study foreign art changes drastically when you have the objects you are studying in your possession.

Repatriation is the first topic that comes up. What to do with objects that museums own as a result of colonialism and imperialism. Who and what are museums for? What systems of power do they uphold? Who gets to benefit from this culture and whose culture are they benefitting from? Professor Crasnow is strongly aligned with the idea that when countries want their artworks back, they should be returned. She acknowledges that museums are extremely white and believes they need to hire a more diverse set of people across the board. Just as in academia, for every culture being studied there should be scholars from both inside and outside of that group. We discussed a situation from a few years ago when the Brooklyn Museum hired a white curator for their African art collection. People were, quite understandably, angry at the decision. She told me about how during her graduate studies, friends of hers were being pushed to study art that related to aspects of their identity, despite it being outside of their interests. Hiring more people of color for every position, not just the ones that tokenize us, would give aspiring curators of color more opportunities as well. It would matter less that we had specific people to fill specific roles.

The last question I had was on white curators and repatriation. Where is the line between being transparent and being performative? Professor Crasnow believes that a practice is transparent so long as it allows for feedback and criticism. There is something valuable about that kind of transparency. It shows pure intentions and possibility. It sets an example for other institutions to follow. If you respond to the feedback you receive, that is transparency. If you are open to all the ways in which your work can be interpreted, that is transparency but if not, it indicates that you are interested in one narrative or perception.

Palestine has been under occupation since 1948. Many of the systems that govern the study of art are used to further colonial agendas. In her book Portrait of a Thief, Grace D. Li writes “China and its art, its history, would always be a story of greatness. It would always be a story of loss.” It is in studying a country currently being colonized that we see how important it is to have new, anti-colonial ways of approaching

More from UMMA