Reflecting on the Women of UMMA’s Galleries

In honor of Women’s History Month, I decided to put aside an hour to walk through the U-M Museum of Art’s galleries and reflect on the depictions of women in the art on display.

Below are the pieces which, for varying reasons, caught my attention.

Cascading Celestial Giant II – Ayana V. Jackson

I was immediately struck by Cascading Celestial Giant I and II by Ayana V. Jackson in the Davidson Gallery, as part of the Unsettling Histories exhibition. These accompanying pieces are immensely powerful in both appearance and meaning. Massive, fluid white skirts dominate the frame, starkly contrasted by the dark background. The huge scale archival pigment prints showcase a somber figure with eyes cast gently downwards. Examination of the description reveals that these images are of the artist herself, adorned as the Senegalese goddess Mame Cumba Bang: protector of the city of Saint-Louis and special icon for fishermen. Inspired by legend surrounding enslaved African women drowned during the Middle Passage due to their pregnancy, this piece represents hope in the face of adversity and continues a tradition of resistance through the arts when our greatest institutions fail to recognize the horrors of our past.

Pieces like these are so important in giving visibility to narratives which are so often overlooked or censored in media, particularly the voices of women of color. This piece especially sticks out to me as it is juxtaposed alongside depictions of well known American icons whose problematic histories are often obscured, such as the portrait of Martha Washington: seen as a maternal figure to the early United States, but lesser known as a slave owner.

Nydia, the Blind Flower Girl of Pompeii – Randolph Rogers

Another depiction of a powerful woman, Nydia, the Blind Flower Girl of Pompeii by Randolph Rogers located in the apse has been one of my favorite pieces at UMMA. One of 167 replicas, it is easy to see why this was one of the most popular American statues of the 19th century. There is something captivating about this depiction of Nydia, brow furrowed as she attempts to lead her companions out of the burning city of Pompeii, fearless in the face of her inevitable doom. Perhaps it is her noble leadership, or her compassion as she offers what hope she can to her condemned friends. This character has captured the attention of artists across multiple centuries, first appearing in the novel The Last Days of Pompeii by Lord Edward Bulwer-Lytton in 1834. Nydia continues to capture the attention of visitors today, located in museums around the country and providing a paradigm of the courage which is so often attributed to masculinity in popular culture.

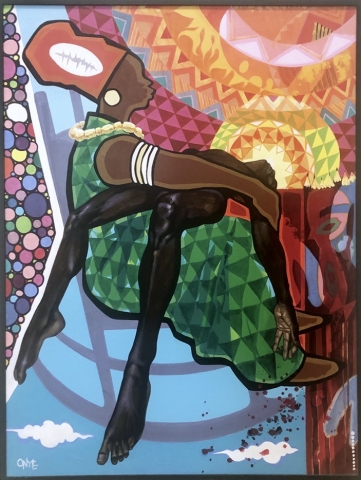

Detroit/Soweto Pieta – Jon Onye Lockard

A differing depiction of courage is presented in We Write to You About Africa. Jon Onye Lockard’s Detroit/Soweto Pieta shows a grieving mother as she cradles the body of her deceased son. Modeled after compositions typical of the Virgin Mary and the crucified Jesus in Christian culture, this painting examines the irony behind the violence in Soweto, South Africa and Detroit, as well as violence directed towards Africans and African Amerricans more broadly. Early colonial movements often used religious conversion as an excuse for their actions, claiming a mission of “saving” via conversion whilst contradicting the same values they claimed to advocate with wanton violence and destruction, and much the same rhetoric appears today as racially motivated violence by law enforcement often happens under calls for “safety.” Here, Lockard appeals to viewers by documenting the suffering of a mother whose greatest love has been stolen.

.

.

Figure of a Girl in Blue (portrait of Miss Minnie Clark)– Thomas Wilmer Dewing

Girl in Blue – Chinese

For a much different reason, I was struck by Figure of a Girl in Blue by Thomas Wilmer Dewing and Girl in Blue by an unrecorded Chinese artist.. These pieces echo each other in both content and title. Both are products of male gaze laid bare, a model and a pin-up girl whose identities have been reduced to their garments and sex only, they have been transformed from complex people into “Girl(s) in Blue.” Dewing’s girl became the model for the ideal standard of beauty in 1890s America as the iconic “Gibson Girl,” pressuring women to mold themselves into identical caricatures of a woman, a girl who never really existed. The plaque below the painting describes this woman as “attenuated and ethereal – though also subtly eroticized;” these women must be walking contradictions, distant but beguiling, untouchable but also within reach. These paintings do not tell a story about these women, they are not people but rather pictures for their creators and audience’s pleasure alone.

Sophie/Elsie – Mary Sibande

A piece which does tell a rich story is Sophie/Elise by Mary Sibande, part of the exhibition We Write To You About Africa. This piece echoes the hopes and realities of generations of the artists’ female forebears, and Sibande is able to pay homage to and give life to the aspirations of her great-grandmother, a piece in reverence for the perseverance of the women who lived through apartheid. As an observer, this piece asked me to examine my own maternal lineage and feel connected not only to Sophie and Mary but my own grandmother, who raised five children as a single mom during a time (not too long ago) before women could own credit cards independent of a husband. I felt a deep sense of gratitude, as I believe the artist did for her own great-grandmother whilst making this piece, for the women before me who fought for the ability to pursue my own dreams.

Durga on her lion mount – Indian

As I rounded the final corner of the Crumpacker Gallery, I came across what may be my favorite piece from this journey. Durga on Her Lion Mount (artist unknown) sits by the exit to the museum gallery, sitting composed yet ripe with power. Freshly victorious from her battle against the demon Mahishasura, Durga seems unbothered and content, in a take on femininity that is not often portrayed in Western media. Durga is a protector, and rightly so. I felt at ease under her aimable gaze as she wielded a sword and shield upon her steed. Displaying feminine power that was never soft nor meek, Durga’s confidence seemed to emanate from the stone statue.

More from UMMA