Serving the Empire on a Plate: The Charm and Legacy of Blue and White Ware

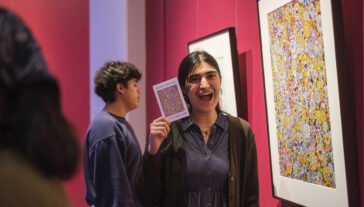

Installed across four different galleries at UMMA, the exhibition Around the World in Blue and White explores the history and influence of blue and white ceramics across the globe.

In the 14th century, blue and white porcelain originated in China and quickly set off a worldwide craze that endures to this day. Made with clay and cobalt from the Middle East, blue and white ware was first commissioned by Muslim merchants living in Chinese port towns during the Yuan Dynasty of Mongol rule. Granted the active trade networks during that historical period, the pots soon found their way to Southeast and East Asia, the Middle East, the eastern coast of the African continent, and then to Europe and North and South America.

Curious about why and how blue and white ware captured everyone’s heart and its legacy, I interviewed Christian de Pee, my history professor specializing in Chinese history from the 8th to 14th century.

According to Professor de Pee, there are two reasons why porcelain is so attractive.

First, the texture of the porcelain is very hard, which allows it to be made into a thin substance that can take the form of exquisite shapes such as long spouts of teapots. Back then, Europeans only had earthenware and therefore found it fascinating that anything made of clay could be so delicate and robust at the same time, allowing all these shapes to be made.

Second, in pre-modern Europe, especially in the 18th century when porcelain became popular, there was a concern with the stupefying effects of alcohol. Water thus became an attractive alternative when added tea as an ingredient. At the same time, coffee also gained popularity as a drink that increased productivity and played an essential role in the movement of the Enlightenment, which inspired new political ideas and literary development. Therefore, porcelain played a vital role in European life and history.

Nevertheless, a trade imbalance existed between Europe and China despite the desire for porcelain, leading to European economic resentment and anger against China’s trade restrictions. Believing that the price of porcelain was artificially high and that they were deceived, Europeans began learning how to make porcelain themselves. Although the process took some time, Wedgewood, the British porcelain company, came into existence. Hence, Wedgewood began manufacturing an imitated version of porcelain, appropriating the original technology, demonstrating feelings of admiration and resentment towards China related to Europe’s colonial attempts. Since then, porcelain technology no longer existed as a secret.

According to Professor de Pee, today, porcelain leaves its most important legacy in modern design. It not only inspired the design of ceramics but also that of furniture and clothing in the early 20th century when there was an imitation of Chinese and Japanese aesthetics in the west.

More from UMMA